Boris Ord’s Adam lay ybownden is a popular Christmas piece amongst amateur and professional choirs alike for its simplicity and and beauty. There have been many other settings of this text by, amongst others, Thea Musgrave and Howard Skempton.

It was in searching for the source of this text that I happened across Thomas Wright’s collection Carols and Songs from a manuscript in the British Museum, a collection of transcriptions from the 14th/15th century Manuscript Sloane MS 2593, currently kept in The British Library. I have written two settings which you can find out about here and here.

But, how to pronounce the Middle English? It is one of those settings that choirs often perform assuming a sort-of modern English pronunciation.

Having looked into how to pronounce Britten’s Wolcum Yule, which is based on a text from the same collection (see this blog post). I thought I’d follow on with this little Middle English gem.

If you’re impatient to skip to the transliteration, please by all means click here.

The principals

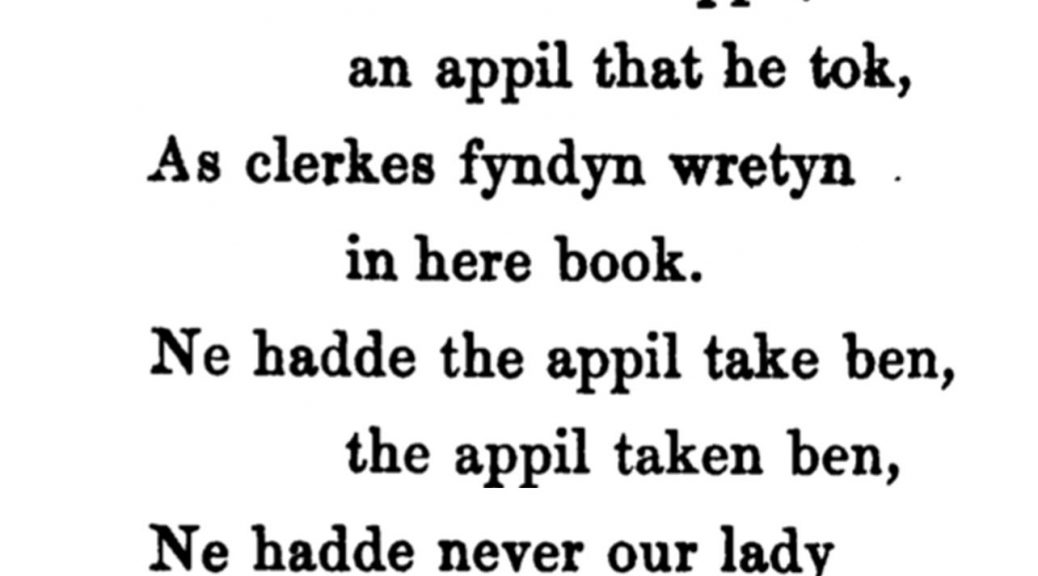

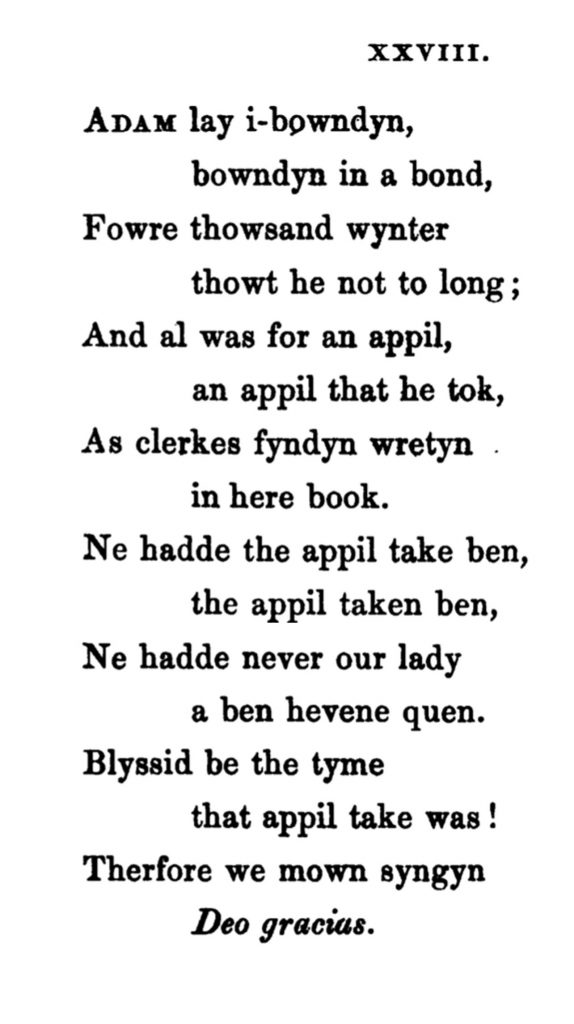

I am going to be using the same principals as my Wolcum Yule post, so the first thing we’ll need is the source text, or rather the copy I have from Songs and Carols from a 15th Century Manuscript in the British Museum which takes it from the Sloane MS 2593, now residing The British Library:

Let’s start with the first line:

Adam lay i-bowndyn

Note straight away the difference in spelling from the Orde (Adam lay ybounden). It could be that Orde used a different source. It’s unclear at this point. We shall use this source however, as it’s all I have presently.

The Middle English Alliterative Poetry blog asserts that “Consonants are pronounced as in Modern English except ȝ/gh, which represents /x/, the guttural sound in German Loch“, which for consonants makes our job here pretty easy.

Vowels are more difficult to ascertain, and most medieval pronunciation guides talk about short vowels and long vowels. To understand what that means here is a (hopefully) useful chart:

| Modern Vowel | Short (both) | Modern Long example | Middle Long |

| a | cat, fat | mate, date | father |

| e | bet, fret | meet, feed | blame, fame |

| i | sit, fit | sight, might, white | wheat, meet |

| o | dot, trot, lot | boat, load, home | shoe, loo, boo |

| u | but, mull | mule, fool, lute | flour, How, |

Determining which vowels are short and long is more tricky but so long as there is a modern equivalent, you can refer to that modern world as it is etymologically derived. These vowels in bold are long, and underlined are short:

Adam l[ay] [i]-b[ow]nd[yn]

Adam lay bound

[i] – following the forms of binden in this entry on Middle English Compendium I would hazard that this is interchangeable with a y or a yogh (ȝ) character which means it should be long e.g. pronounced ee in middle English.

[yn] – similarly this is a common inflection at the end of the word, the word itself being “bownd”. The presence of an n suggests to me that this inflection should be sung as part of the meter of the song.

[ay] – diphthong of the two long vowels a (father) and i (meet)

[ow] – This diphthong is interchangeable with ou. Dipthongs are pronounced by adding the two long vowels together so thou is o (shoe) + u (flour), to sound like modern English grow, according to Middle English Alliterative Poetry.

Rather than delve into the tricksy and obscure world of the IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet), here is a likely transliteration (i.e. to be read out as if it were modern English):

Adam lahy eebohndin

Now that we’ve got the principles and method down, let’s investigate the rest of this short poem:

| ADAM l[ay] i-b[ow]ndyn, b[ow]ndyn in a bond, F[ow]r[e] th[ow]sand wynter th[ow]t he not to long; And al was for an appil, an [appul] that he tok, As clerkes fyndyn wretyn in her[e] book. [Ne] hadd[e] the appil tak[e] ben, the appil taken ben, [Ne] hadd[e] never [ou]r lady a ben heven[e] quen Blyssid be the tym[e] that appil tak[e] was! Th[ere]for[e] we [mown] syngyn D[eo] gracias | ADAM lay bound,

bound in a bond, Four thousand winter thought he not to long; And all was for an apple, an apple that he took, As clerks find written in here book. Nor had the apple taken been, the apple taken been, Nor had never our lady a been heaven queen Blessed be the time that apple taken was! Therefore we [shall] sing Deo gracias |

[appul] – alternative spelling of apple. It’s not clear whether this is a spelling mistake or a deliberate other pronunciation of the word. According to the Middle English Compendium it refers to “Any kind of fruit” and of course the forbidden fruit of paradise to which it refers here. I’m taking it at face value here

[Ne] – this word means “nor”. It’s not clear whether it would be long or short but looking at the other word forms in Middle English Compendium ni, nen, nin and also its elision forms e.g. nafter (nor after) would suggest a schwa, or short form, So I’m guessing it would be short vowel eh as in bread. Like a lot of Middle English pronunciation, it goes against my instincts (I’ve always thought of it as ney)

[ere] – as most guides assert, all of the consonants are pronounced in Middle English, and all Rs are rolled. In this case where in modern English ere results in a long voiced r consonant, this should result in vowel-rolled R- vowel. If we think of There and fore being two distinct words as part of a portmanteau then the last vowel of there is probably an inflection, my guess for this is Ther*[e]for*[e] i.e. the e after the initial r is a schwa (neutral vowel) and probably short.

[mown] – I’ve seperated this out as it’s a curious word (meaning must, or shall) that still exists in some dialects. In northern England for example “mun”. According to my own assumptions the pronunciation here should be “mohn” but perhaps it should be more like möen

[eo] – this transliteration assumes that Latin follows the same rules as Middle English at this point. Conveniently this diphthong comes out with the same first vowel as we would naturally pronounce it – D-ay-(oh in modern English, oo in Middle English)

Summary and Transliteration

Here is my transliteration of Adam lay I-bownden. It assumes a neutral British accent when reading out.

Adam lahy eebohndin

bohndin in a bond,

Fohr*[e] thohsand winter

thoht hei not too long;

And all was for an appil,

an appul that hei took,

As cler*kes feendin wr*etin

in heyr*[e] bohk.

Ne had[e] the appil tahk[e] beyn

the appil tahken beyn,

Ne hadd[e] never ohr* lahdy

a beyn heaven[e] queyn

Blissid bey the teem[e]

that appil tahk[e] was!

Ther*[e]for*[e] wey mohn singin

Dayoo Gr*aceeas

[e] = schwa neutral vowel inflection. Not necessarily said and possibly left out mostly when singing, depending on the meter scheme.

r* = rolled R

While it is seductive to try and use these pronunciations in practice, there are definite problems with knowing where to place extra syllables. It would be fun to try, but this is meant as more of an exercise in curiousity.

I am no expert in Middle English Pronunciation and have simply joined dots that are readily available on the internet. If you know better and have anything to add or change, please do leave a comment, or contact me.